Following is a extract of my speech to a course of Geopolitical Economy at Aschaffenburg University on 13 Jan 2026.

Also Podcast Link:https://open.spotify.com/episode/2CtEykBQj48loF59X1rcR7?si=TrLcERSCT32SSv4tOAbpMA

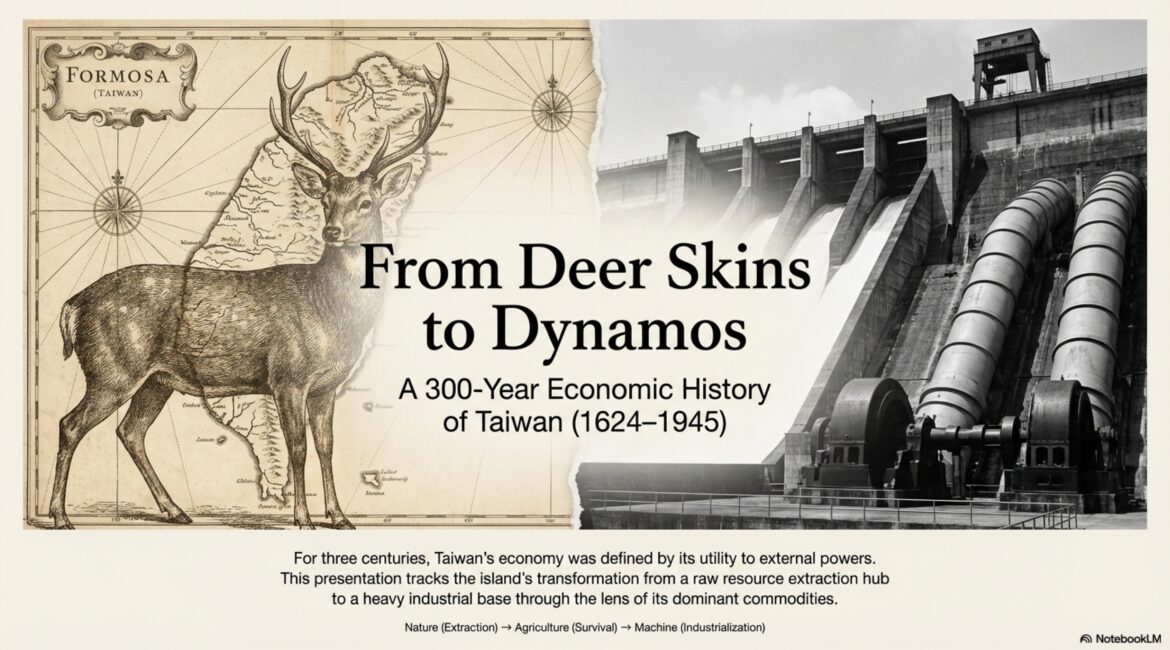

On the opening page, two images immediately set the tone of Taiwan’s economic history. On the right stands a sika deer, once abundant across the plains of Taiwan before the seventeenth century. On the left appears a hydraulic power dam, constructed during the Japanese colonial period to generate electricity and support heavy industry. These two images tell a powerful story. Within roughly three centuries—more precisely, within just over one hundred years of concentrated transformation—Taiwan moved from a landscape economy based on extraction to an industrial society equipped with modern infrastructure. The long interim period under early Qing rule, marked by limited state investment, explains why this transformation was delayed rather than continuous.

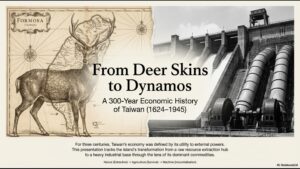

The Era of Extraction: Dutch Colonial Taiwan (1624–1662)

The first phase of Taiwan’s economic history begins with Dutch colonization in 1624. This period coincided with the Thirty Years’ War in Europe, which also functioned as a war of independence for the Netherlands against the Habsburg Empire. As a small maritime nation confronting a global hegemon, the Dutch adopted an innovative strategy: disrupting Iberian trade routes rather than confronting imperial power directly.

This strategy gave rise to the Dutch East India Company (VOC), a corporate-military enterprise designed to control trade nodes across Asia. Taiwan emerged as a profitable outpost within this system. The core economic activity during this period was extraction, most notably the hunting of sika deer. Deer hides were highly valued in Japan, where samurai used them as decorative and functional elements of armor. In exchange, the Dutch obtained Japanese silver, which could then be traded in China for silk and porcelain. These luxury goods, once shipped back to Europe, yielded enormous profits in Amsterdam. Taiwan thus became an intermediary node in a transcontinental trade circuit linking Japan, China, Southeast Asia, and Europe.

Fortress Economies and Military Colonization: The Koxinga Period (1662–1683)

The second phase began when Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong) expelled the Dutch in 1662. Taiwan became a military stronghold for a regime attempting to resist Qing conquest. Survival, rather than profit maximization, defined the economic logic of this period. Soldiers were transformed into farmer-soldiers, cultivating land to supply the army. Fortresses became centers of production as much as defense.

Cut off from the mainland due to Qing coastal blockades and lacking external support, Koxinga’s regime relied on limited international trade to sustain itself. Notably, this period witnessed Taiwan’s first formal international arms trade agreement, signed with the British East India Company, marking Taiwan’s earliest appearance as a treaty-signing entity in global commerce.

The Era of Integration: Taiwan under Early Qing Rule (1683–1860)

After Qing forces conquered Taiwan in 1683, the island entered a long period of relative neglect. The Manchurian ruling elite, a demographic minority governing a vast Han population, viewed Taiwan primarily as a frontier zone. Stability, rather than development, was the priority.

Nevertheless, economic integration proceeded organically. A clear division of labor emerged: northern Taiwan specialized in rice cultivation, while southern Taiwan focused on sugar cane. These products were exported to China’s southeastern coastal provinces, particularly Fujian and Guangdong, in exchange for construction materials and manufactured goods unavailable locally. While this era lacked major institutional investment, it laid the groundwork for regional specialization and internal market integration.

Entry into the Global Economy: Treaty Ports and Tea (1860–1895)

Taiwan’s fourth economic phase began with the Treaty of Tianjin in 1860, which opened several ports to foreign trade, including Keelung. For the first time, Taiwan became fully integrated into global markets. Tea emerged as the symbolic commodity of this era. Taiwanese oolong tea gained international recognition, with exports accounting for more than half of Taiwan’s total export value.

Foreign merchants played a decisive role in this transformation. One prominent figure was John Dodd, an American trader who successfully branded Taiwanese oolong tea for Western markets. Other important export commodities included sugar and camphor, the latter being a crucial input for celluloid, film, and gunpowder in the industrial age.

The Seed of Modernization: Late Qing Reforms

In the final decade of Qing rule, Taiwan was elevated to provincial status, triggering overdue modernization efforts. These reforms were closely tied to regional geopolitical pressures. Following forced encounters with Western powers in the mid-nineteenth century and conflicts involving the Ryukyu Islands, the Qing court recognized Taiwan’s strategic maritime importance.

Governor Liu Mingchuan spearheaded modernization projects that were politically impossible on the mainland. Taiwan’s first railway, stretching from Keelung to Hsinchu, symbolized a dramatic institutional shift. Infrastructure development, once seen as socially disruptive, was tolerated—and even encouraged—on the island.

Industrialization under Japanese Colonial Rule (1895–1945)

Following Japan’s victory in the First Sino-Japanese War, Taiwan entered its most transformative economic phase. Japanese authorities viewed Taiwan as both a strategic asset and a showcase colony. Massive capital investment flowed into infrastructure, administration, and industry. Standardized weights and measures, a gold-based currency system, and modern banking institutions were introduced. The north–south railway was completed, integrating the island economically.

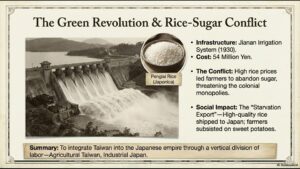

Agricultural production was reorganized to serve imperial needs. Sugar production was tightly controlled through regional monopolies, limiting farmers’ bargaining power but ensuring price stability. Rice cultivation was expanded and modernized through major irrigation projects, including the Wusanto Dam and the Chianan Irrigation System, then the largest in Asia.

By the 1930s, Taiwan had become a key component of Japan’s war economy. Heavy industries emerged in southern Taiwan, particularly around Kaohsiung. Hydroelectric dams supplied the electricity required for aluminum refining, aircraft production, and chemical industries. In 1939, industrial output briefly surpassed agricultural production, marking Taiwan’s transition into an industrial economy.

From Historical Foundations to a High-Tech Present

Across these successive periods, each economic structure prepared the conditions for the next. Taiwan’s modern high-tech economy, often perceived as a post-war miracle, was in fact built upon layered historical foundations established over centuries. Despite prolonged external pressures and geopolitical threats, Taiwan has repeatedly demonstrated resilience and adaptability. That legacy continues to shape its economic trajectory today.